New research by an international team of scientists shows how marine organisms were forced to 'reboot' to survive following the asteroid impact 66 million years ago which killed three quarters of life on earth.

Researchers from the University of Southampton and UCL, along with colleagues in Paris, California, Bristol and Edinburgh used an exceptional record of plankton fossils and eco-evolutionary modelling techniques to examine how organisms behaved before and after this extinction event - and why some survived and some didn't.

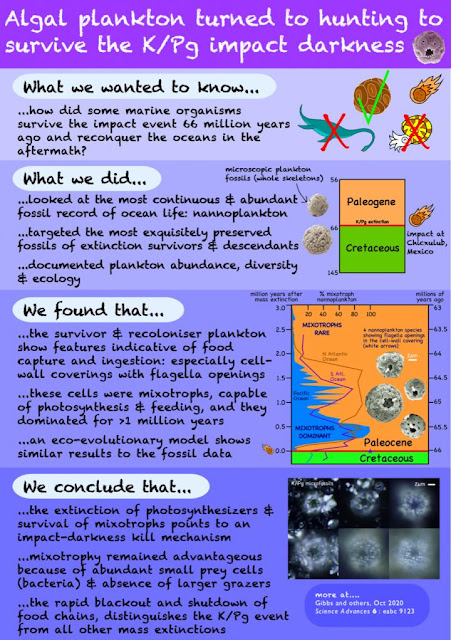

The team found that prior to the asteroid impact, species of nannoplankton - microscopic algae - were exclusively reliant on harnessing energy from sunlight (photoautotrophs), but those living afterwards were capable of capturing food and eating it in addition to using photosynthesis to feed (mixotrophs). This suggests the blocking of light from the sun played an important role in killing off some species and over time, encouraging others to evolve and adapt.

The research team's breakthrough came when they found that many of the nannoplankton skeletons (coccospheres) post mass-extinction included a large hole, indicating the position of flagella - tiny tail like structures used by the algae for movement and feeding. This indicates these microscopic organisms, which survived the asteroid strike, were capable of hunting and ingesting food.

"Those species that were lost at the mass extinction show no evidence of a mixotrophic lifestyle and were likely to be completely reliant on sunlight and photosynthesis," explains Dr Samantha Gibbs of the University of Southampton. "Fossils following the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction show that mixotrophy dominated and our model indicates this is because of the exceptional abundance of small prey cells - most likely surviving bacteria - and reduced numbers of larger 'grazers' in the post-extinction oceans."

Opposing evolutionary forces led to the emergence of more diverse feeding strategies and eventually a return to greater reliance on photosynthesis in open ocean nannoplankton. Most nannoplankton today only photosynthesise. So, what caused this devastating mass extinction of photoautotrophs and other species?

The simple answer is a lack of light. The K/Pg event was triggered by an asteroid impact that formed the Chicxulub crater in Mexico, and is well known for the extinction of dinosaurs, plesiosaurs, ammonites and many other groups.

"This huge impact flung vast amounts of debris, aerosols and soot into the atmosphere, causing darkness, cooling and acidification over days and years," says Paul Bown, Professor of Micropalaeontology at UCL. "The significant bias found in the nannoplankton extinctions - removal of open-ocean photoautotrophs but survival of mixotrophs that could hunt and feed - can only be fully explained by the darkness caused by the asteroid impact acting as a kill mechanism."

|

| Graphic explaining the research method and findings [Credit: Gibbs et al., 2020] |

Samantha Gibbs adds: "This 'blackout' or shutdown of primary productivity would have been felt across all of Earth's ecosystems and reveals that the K/Pg event is distinct from all other mass extinctions that have shaped the history of life, both in its rapidity, related to an instantaneous impact event, and its darkness kill mechanism, which shook the foundations of the food chains. The K/Pg boundary event likely represents the only truly geologically instantaneous mass extinction event."

Findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: University of South Hampton [October 30, 2020]