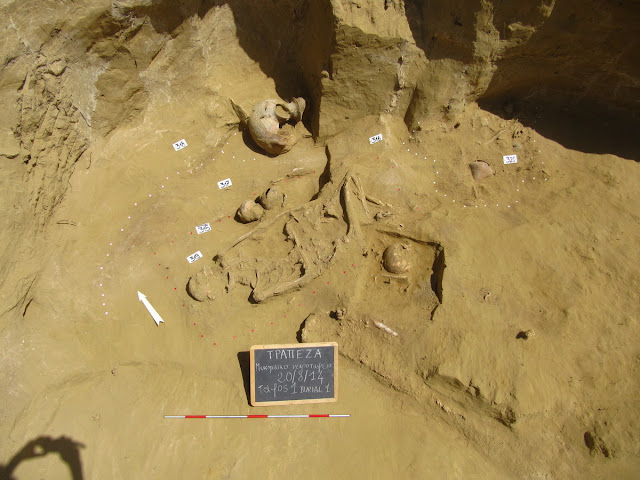

A gem was found in the The Archaeological Sifting Project in the Tzurim Valley National Park, carried out under the auspices of the City of David and the Nature and Parks Authority. The gem features an engraved portrait of the god Apollo. According to researchers, this rare find is the third secured gem sealing (also called an intaglio which is a gem with a design carved into the upper side of the stone) from the Second Temple period to have ever been discovered in Jerusalem.

|

| This 2,000-year-old gem seal bearing the image of Apollo was found in earth excavated from the foundations of the Western Wall in the Old City of Jerusalem [Credit: Eliyahu Yanai, City of David] |

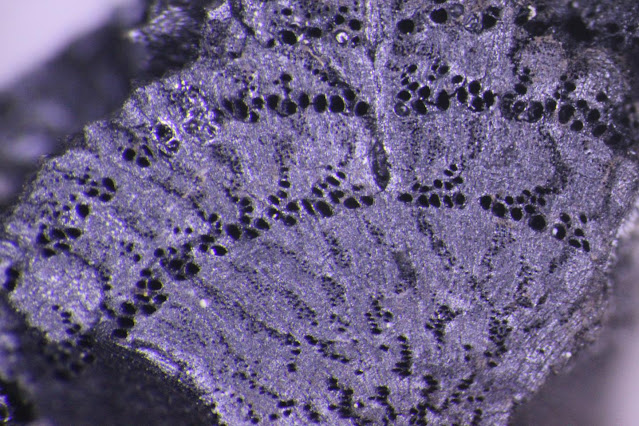

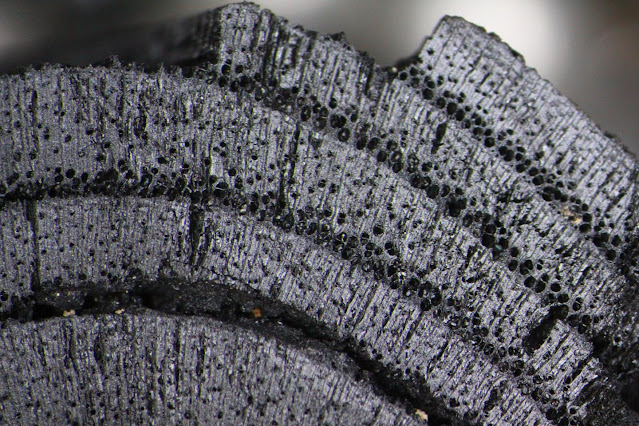

The gem is cut from dark brown jasper, and has remnants of yellow-light, brown, and white layers. In antiquity, jasper was considered a precious stone. The gem seal was embedded in a ring, dated to the 1st century CE (Second Temple period).

The gem is tiny, oval-shaped, 13 mm long, 11 mm wide, and 3 mm thick. Because the gem is an intaglio, its main function was as a stamp to be used on soft material, usually beeswax, for personal signatures on contracts, letters, wills, goods or bundles of money. The gem features an engraving of Apollo’s head in profile to the left, with long hair flowing over a wide, pillar-like neck, a large nose, thick lips, and a small prominent chin. The hair is styled in a series of parallel lines directed to the apex, and surrounded by a braid above the forehead. One line of hair marks a strand that covers the ear; long curls flow over part of the neck, reaching the left shoulder. Thin diagonal lines at the base of the head mark the upper end of the garment and the body.

|

| Credit: Eliyahu Yanai, City of David |

According to researchers - archaeologist Eli Shukron, Prof. Shua Amorai-Stark, and senior archaeologist Malka Hershkovitz - although Apollo is an Olympian deity of the Greek and Roman cultures, it is highly probable that the person wearing the ring was a Jew.

In the opinion of archaeologist Eli Shukron, who conducted the excavation in which the gem was found: “It is rare to find seal remains bearing the image of the god Apollo at sites identified with the Jewish population. To this day, two such gems (seals) have been found in Masada, another in Jerusalem inside an ossuary (burial box) in a Jewish tomb on Mount Scopus, and the current gem that was discovered in close proximity to the Temple Mount.” Mr. Shukron added: “When we found the gem, we asked ourselves ‘what is Apollo doing in Jerusalem? And why would a Jew wear a ring with the portrait of a foreign god?’ The answer to this, in our opinion, lies in the fact that the owner of the ring wore it not as a ritual act that expresses religious belief, but as a means of making use of the impact that Apollo’s figure represents: light, purity, health, and success.”

Prof. Shua Amorai-Stark, a researcher of engraved gems, stated that: “At the end of the Second Temple period, the sun god Apollo was one of the most popular and revered deities in Eastern Mediterranean regions. Apollo was a god of manifold functions, meanings, and epithets. Among Apollo’s spheres of responsibility, it is likely that association with sun and light (as well as with logic, reason, prophecy, and healing) fascinated some Jews, given that the element of light versus darkness was prominently present in Jewish worldview in those days. The fact that the craftsman of this gem left the yellow-golden and light brown layers on the god’s hair probably indicates a desire to emphasize the aspect of light in the god’s persona, as well as in the aura that surrounded his head. The choice of a dark stone with yellow coloring of hair suggests that the creator or owner of this intaglio sought to emphasize the dichotomous aspect of light and darkness and/or their connectedness.”

Source: City of David [October 29, 2020]