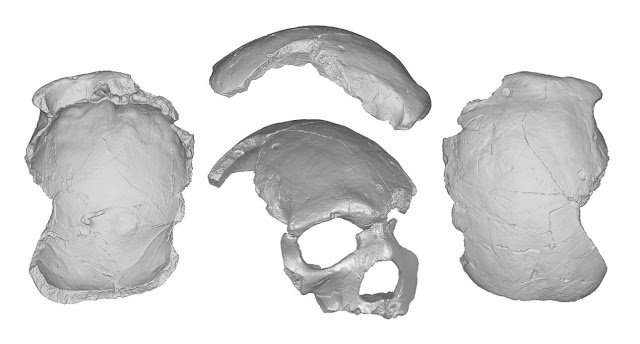

One year after the publication of research on the Xiahe mandible, the first Denisovan fossil found outside of Denisova Cave, the same research team has now reported their findings of Denisovan DNA from sediments of the Baishiya Karst Cave (BKC) on the Tibetan Plateau where the Xiahe mandible was found.

|

| Baishiya Karst Cave [Credit: HAN Yuanyuan] |

The research team was led by Prof. CHEN Fahu from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research (ITP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Prof. ZHANG Dongju from Lanzhou University, Prof. FU Qiaomei from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of CAS, Prof. Svante Paabo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and Prof. LI Bo from University of Wollongong.

Using cutting-edge paleogenetic technology, the researchers successfully extracted Denisovan mtDNA from Late Pleistocene sediment samples collected during the excavation of BKC. Their results show that this Denisovan group is closely related to the late Denisovans from Denisova Cave, indicating Denisovans occupied the Tibetan Plateau for a rather long time and had probably adapted to the high-altitude environment.

Denisovans were first discovered and identified in 2010 by a research team led by Prof. Svante Paabo. Almost a decade later, the Xiahe mandible was found on the Tibetan Plateau. As the first Denisovan fossil found outside of Denisova Cave, it confirmed that Denisovans had occupied the roof of the world in the late Middle Pleistocene and were widespread. Although the Xiahe mandible shed great new light on Denisovan studies, without DNA and secure stratigraphic and archaeological context, the information it revealed about Denisovans was still considerably restricted.

|

| Collecting sediment DNA samples [Credit: HAN Yuanyuan] |

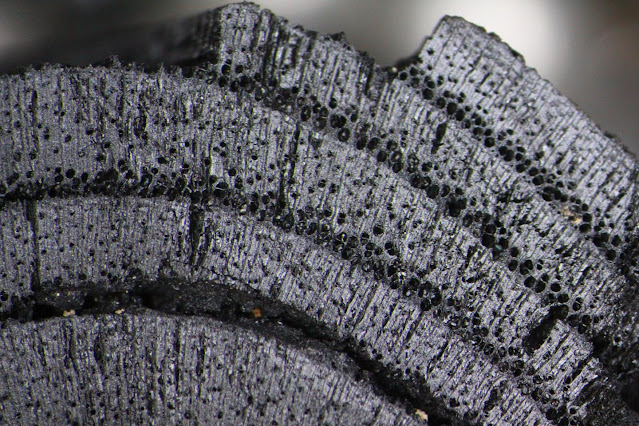

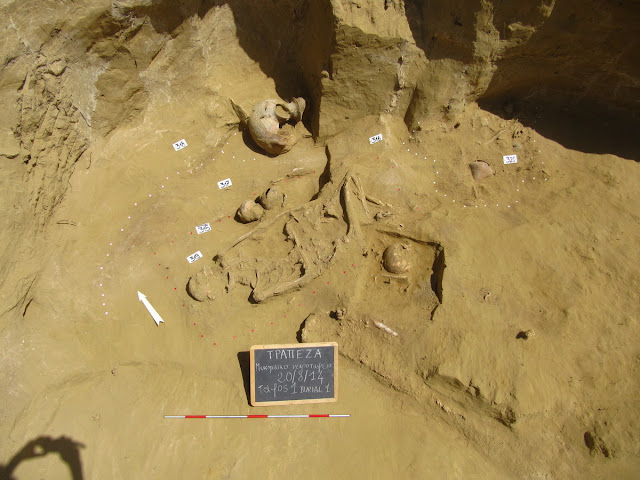

In 2010, a research team from Lanzhou University led by Prof. CHEN Fahu, current director of ITP, began to work in BKC and the Ganjia basin where it is located. Since then, thousands of pieces of stone artifacts and animal bones have been found. Subsequent analysis indicated that the stone artifacts were mainly produced using simple core-flake technology. Among animal species represented, gazelles and foxes dominated in the upper layers, but rhinoceros, wild bos and hyena dominated in the lower layers. Some of the bones had been burnt or have cut-marks, indicating that humans occupied the cave for a rather long time.

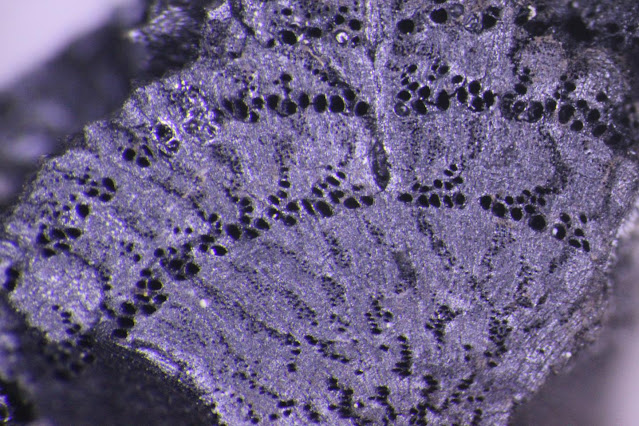

To determine when people occupied the cave, researchers used radiocarbon dating of bone fragments recovered from the upper layers and optical dating of sediments collected from all layers in the excavated profile. They measured 14 bone fragments and about 30,000 individual grains of feldspar and quartz minerals from 12 sediment samples to construct a robust chronological framework for the site. Dating results suggest that the deepest excavated deposits contain stone artifacts buried over ~190 ka (thousand years). Sediments and stone artifacts accumulated over time until at least ~45 ka or even later.

To determine who occupied the cave, researchers used sedimentary DNA technology to analyze 35 sediment samples specially collected during the excavation for DNA analysis. They captured 242 mammalian and human mtDNA samples, thus enriching the record of DNA related to ancient hominins. Interestingly, they detected ancient human fragments that matched mtDNA associated with Denisovans in four different sediment layers deposited ~100 ka and ~60 ka.

|

| Preparing sediment samples in IVPP cleanroom [Credit: WANG Xiao] |

More interestingly, they found that the hominin mtDNA from 60 ka share the closest genetic relationship to Denisova 3 and 4 - i.e., specimens sampled from Denisova Cave in Altai, Russia. In contrast, mtDNA dating to ~100 ka shows a separation from the lineage leading to Denisova 3 and 4.

Using sedimentary DNA from BKC, researchers found the first genetic evidence that Denisovans lived outside of Denisova Cave. This new study supports the idea that Denisovans had a wide geographic distribution not limited to Siberia, and they may have adapted to life at high altitudes and contributed such adaptation to modern humans on the Tibetan Plateau.

However, there are still many questions left. For example, what's the latest age of Denisovans in BKC? Due to the reworked nature of the top three layers, it is difficult to directly associate the mtDNA with their depositional ages, which are as late as 20-30 ka BP. Therefore, it is uncertain whether these late Denisovans had encountered modern humans or not. In addition, just based on mtDNA, we still don't know the exact relationship between the BKC Denisovans, those from Denisova Cave in Siberia and modern Tibetans. Future nuclear DNA from this site may provide a tool to further explore these questions.

The study was published in Science.

Source: Chinese Academy of Sciences [October 30, 2020]